This copy is intended for historical and educational purposes, and is used in accordance with the fair-use provisions of copyright law.

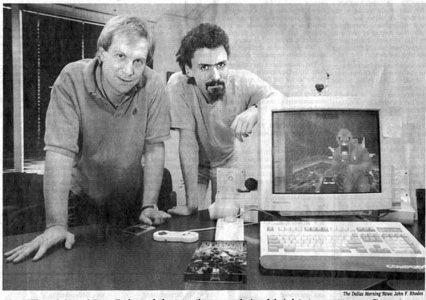

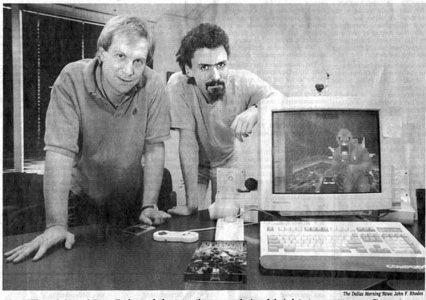

id Software has no marketing department, no executive offices, no sales force. Just computers and phone lines.

By linking the two, the Mesquite-based company has sent a shockwave through cyberspace. It has created a game for home computers that experts consider stunning and users can't wait to play.

And to ensure success, id gives the game away.

"Everyone is talking about the power of the information superhighway," said Jay Wilbur, id's chief executive officer. "We're the living proof."

In five months, id's latest effort, Doom, has become the nation's third most popular entertainment program. It's making big money by offering free samples of the game's first part in the thousands of places and then selling the complete version directly to eager buyers.

Mr. Wilbur and his four partners - none older than 32 - won't discuss sales figures but note proudly the new homes they're building and the $200,000 Ferraris in the parking lot.

Their recipe for success is simplicity, from the play of the game to its marketing.

"We don't waste time on a whole lot of story line," Mr. Wilbur said. "Our manual could be as simple as: 'If it moves, kill it.'"

Armed with pistols, shotguns, rockets and chainsaws, players blast through an Earth colony on Mars that has been overrun by monsters. If that's not enough, players can hunt and shoot one another by connecting over telephone lines.

The phone lines are also how customers can get the game for free, by calling virtually any computer network or bulletin board service across the country and downloading it.

Since the early days of personal computers, programmers have given away their creations and asked for donations if people like the product. It was called shareware. But few products made money, and those that did became successful by finally getting software stores to carry the program.

id is the exception, said Terri Childs, spokeswoman for the Software Publishers Association, an international trade organization of more than 1,100 developers.

"The idea of shareware and marketing are not two ideas that share the same breath," she said. The fact that id has done this for more than one product shows that they're clearly onto something."

id's first hit, in 1991, was a game called Wolfenstein, in which players hunted Nazis in an old castle. As with Doom, id gave away the first episode Wolfenstein, a fully playable version that for many would be more than enough fun.

But hard-core users could buy more episodes, and they did. More than 150,000 users shelled out the required $50, a few dollars more than most games on software store shelves.

As word spread that id was preparing a sequel named Doom, thousands of suggestions poured in on computer networks and bulletin boards.

"If we sold it through the stores, we'd get maybe $4 per unit," Mr. Wilbur said. "This way we may sell fewer - although we don't - but we make more."

By the time Doom was released Dec. 10, demand was so immediate that it brought part of the worldwide Internet - a massive web of supercomputers and networks - to its knees. On its first day of release, the University of Wisconsin's computer was overwhelmed by 8,000 people simultaneously trying to download the game via its bulletin board on Internet, id employees said.

On commercial networks such as America Online, users crammed into electronic "rooms" waiting their chance to download the program. Depending on the speed of the user's modem, transfer takes one to four hours.

"It was a mob scene the night Doom came out," said Debbie Rogers, forum leader of America Online's game section. "If we weren't on the other side of a phone line, there would have been bodily harm."

About 20,000 America Online users have snapped up copies. id estimates that 1.3 million copies of the free version are now loaded on personal computers.

Players inevitably talk about the action and strategy, but the appeal goes beyond violence, Ms. Rogers said.

The graphics are detailed and flow as smoothly as in an arcade game. The sound effects are so complete that the user hears his own character panting after a hard run.

"It's unlike anything people have ever seen before," Ms. Rogers said. "The first time you play, it's 'Oh, my god!'"

Part of that effect is the gore. Everything bleeds, oozes or explodes, which has raised the ire of those concerned about violence in video and computer games.

id labels the program with warnings about the violence. Nonetheless, some parents have been stunned by what their children downloaded off a computer service. At least one parent complained to America Online officials.

Mr. Wilbur said the company has received no complaints, but the nature of the game concerns those who monitor violence in computer and video games.

"We're dehumanizing our kids," said Roger Kallenberg, a member of the Dallas-based Zero Tolerance for Violence organization. "They're sort of practicing on a game - blowing up monsters, killing everything. How can it help turn them into responsible, law-abiding, tolerant adults?"

Mr. Kallenberg doesn't fault id or its distribution methods. He blames the parents whose children download the game.

"Parents need to get involved. They need to learn how to use the computers their kids have," He said. "These computers don't fall off trees....They dump them in their kids' rooms. It's up to the parents to take responsibility."

Companies that manufacture arcade games aren't concerned about the violence. They have flooded id with offers to put Doom on a commercial video machine.

Books and magazines are in production with play tips and secret codes. Even Hollywood producers have taken notice, proposing an action movie based on the game, Mr. Wilbur said.

The success has taken id by surprise, said John Romero, another partner. They have fielded offers from venture capitalists and partnership proposals form other companies, he said, but the id partners are set in their ways.

"We're going to make lots of money doing it our way," he said. "There's no need to sell out."

In part, that means forgoing the trappings and tools of a mainstream software company.

"Sure we have a research department - us," Mr. Wilbur said. "It comes down to: 'Do we think this is cool? Let's do it.'"

"We have no organizational chart. We still vote each week if it's Coke or Pepsi in the fridge."

Work is already under way on Doom II, to be released later this year, he said. But no sneak previews are being offered.

"Our customers trust us to make it bigger, badder, better," he said. "Our way."